Astronomers studying the outskirts of a distant galaxy have discovered the galaxy sits in a serene ocean of gas.

The massive galaxy, which is about four billion light-years from Earth, is surrounded by a halo of gas that is much less dense and less magnetised than expected.

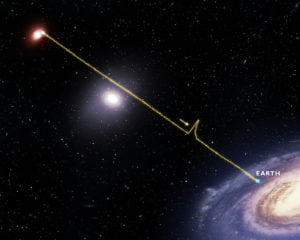

An artist’s impression of Fast Radio Burst 181112 travelling through the halo of a galaxy 4 billion light-years from Earth. Credit: © J. Josephides, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology.

The finding was published today in the journal Science.

Co-author Associate Professor Jean-Pierre Macquart, from the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), said gas on the outskirts of galaxies has traditionally been hard to study.

“The halo of gas can actually extend out 10 times further than the stars in a galaxy, and can contain a substantial amount of the matter that’s in a galaxy,” he said.

“But it’s very difficult to see the gas directly with a telescope.”

Associate Professor Macquart said this discovery was made using a new technique involving fast radio bursts—powerful flashes of energy from deep space.

“Fast radio bursts come from all over the sky and last for just milliseconds,” he said.

“They involve incredible energy—equivalent to the amount released by the Sun in 80 years.

“We’re not sure what causes them, and have only recently been able to pinpoint the galaxies they come from.”

Associate Professor Macquart said the research team looked at how a single fast radio burst distorted as it travelled five billion light-years through the Universe.

Along the way, the burst shot through a galaxy’s halo of gas, like a lighthouse’s beam cutting through the fog.

Associate Professor Macquart said the researchers expected the signal from the fast radio burst to be distorted by the galaxy.

“If you go out on a hot summer’s day, you see the air shimmering and the trees in the background look distorted because of the temperature and density fluctuations in the air,” he said.

“That’s what we thought would happen, that the signal from the fast radio burst would be completely distorted after passing through the hot atmosphere of the galaxy.

“But instead of the stormy galactic ‘weather’ we were expecting, the pulse we observed had travelled through a calm sea of unperturbed gas.”

The finding suggests that galaxy halos are much more serene than previously thought, with gas that is less turbulent, less dense and less magnetised than expected.

One reason astronomers are so interested in galaxy halos is because they can help us understand why material is ejected from galaxies, causing them to stop growing.

University of California Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics J. Xavier Prochaska, who led the research, said halo gas provides a fossil record of these ejection processes.

“So our observations can inform theories about how matter is ejected and how magnetic fields are transported from the galaxy,” he said.

Professor Prochaska said the team now plans to test other galaxies.

“Our research appears to reveal something entirely new about galactic halos,” he said.

“Unless of course, this galaxy happens to be just some weird exception—and with only one object you can’t be sure about that.”

The research used a fast radio burst that was detected in November by CSIRO’s Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), in outback Western Australia.

An artist’s impression of CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope detecting a fast radio burst (FRB). Scientists don’t know what causes FRBs but it must involve incredible energy—equivalent to the amount released by the Sun in 80 years. Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

The telescope is a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which will be the world’s largest radio telescope when it’s built in the next decade.

The study was led by Professor Xavier Prochaska from the University of California and involved 19 researchers from around the world.

We acknowledge the Wajarri Yamaji as the traditional owners of the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory (MRO) site and pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

An artist’s impression of Fast Radio Burst 181112 travelling through the halo of a galaxy 4 billion light-years from Earth. Credit: © J. Josephides, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology.

A fast radio burst leaves a distant galaxy, travelling to Earth over billions of years and occasionally passing through clouds of gas in its path. Each time a cloud of gas is encountered, the different wavelengths that make up a burst are slowed by different amounts. Timing the arrival of the different wavelengths at a radio telescope tells us how much material the burst has travelled through on its way to Earth and allows astronomers to to detect “missing” matter located in the space between galaxies. Credit: CSIRO/ICRAR/OzGrav/Swinburne University of Technology.

Original Publication:

‘The low density and magnetization of a massive galaxy halo exposed by a fast radio burst’, published in Science on September 26th, 2019.

More Information:

ASKAP

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) is the world’s fastest survey radio telescope. Designed and engineered by CSIRO, ASKAP is made up of 36 ‘dish’ antennas, spread across a 6km diameter, that work together as a single instrument called an interferometer. The key feature of ASKAP is its wide field of view, generated by its unique phased array feed (PAF) receivers. Together with specialised digital systems, the PAFs create 36 separate (simultaneous) beams on the sky which are mosaicked together into a large single image.

Multimedia:

An artist’s impression of fast radio bursts in the sky above CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope at the Murchison radio-astronomy Observatory. Each antenna can observe 36 circular patches of sky and in the “fly’s eye” configuration each antenna can be pointed in a different direction, enabling ASKAP to detect the brightest and rarest fast radio bursts. Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

An artist’s impression of fast radio bursts (FRBs). Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

An artist’s impression showing fast radio bursts in the sky above CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope. Fast radio bursts come from all over the sky and last for just milliseconds. ASKAP is located at the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory— the future site in Australia for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA). Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.