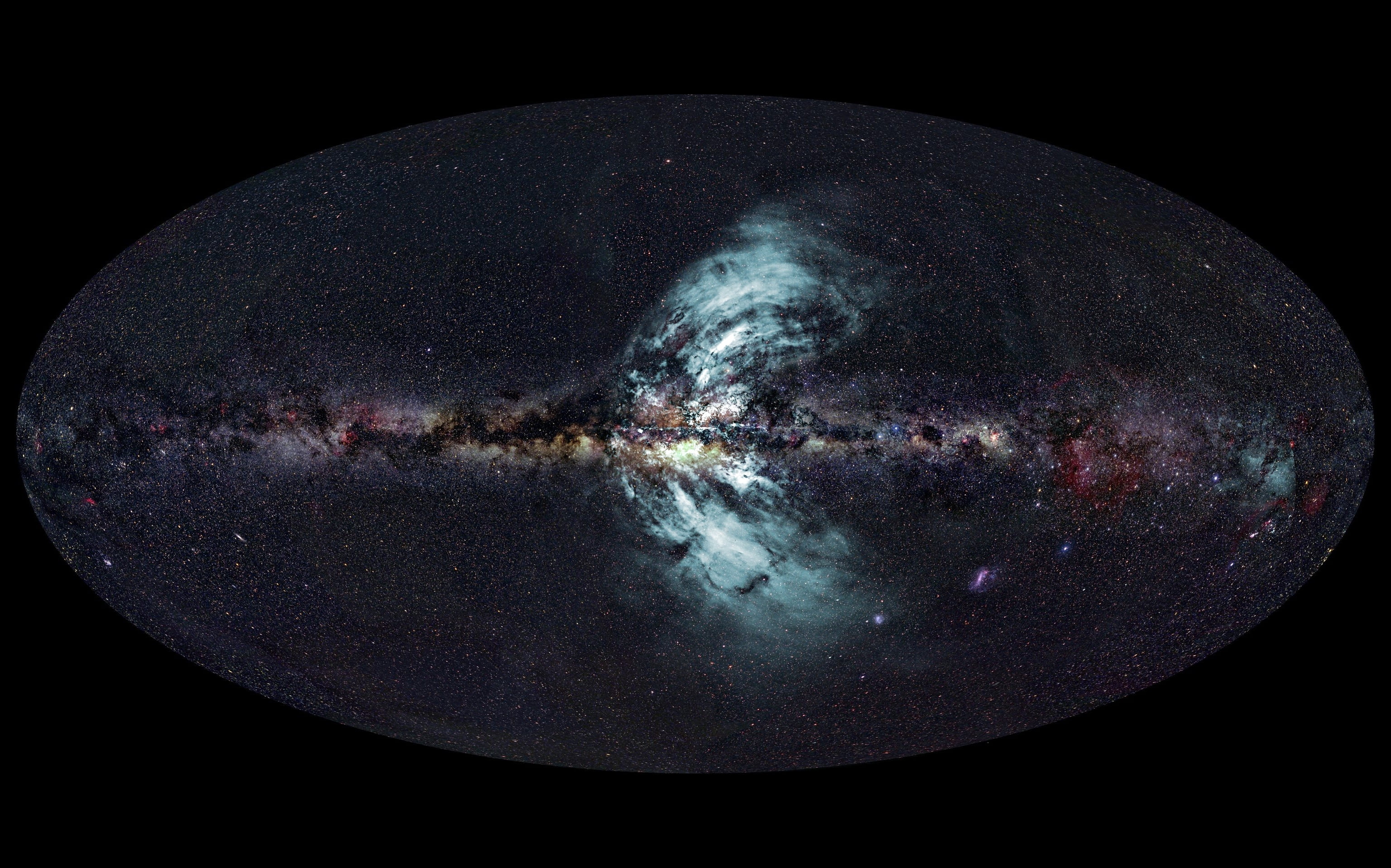

Corresponding to the “Fermi Bubbles” found in 2010, the recent observations of the phenomenon were made by a team of astronomers from Australia, the USA, Italy and The Netherlands, with the findings reported in today’s issue of Nature.

“There is an incredible amount of energy in the outflows,” said co-author Professor Lister-Staveley-Smith from The University of Western Australia node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth and Deputy Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO).

“The source of the energy has been somewhat of a mystery, but we know there is a lot there, about a million times as much energy as a supernova explosion (a dying star).”

From top to bottom the outflows extend 50,000 light-years [five hundred thousand million million kilometres] out of the Galactic Plane. That’s equal to half the diameter of our Galaxy (which is 100,000 light-years—a million million million kilometres—across).

“Our Solar System is located approximately 30,000 light-years from the centre of the Milky Way Galaxy, but we’re perfectly safe as the jets are moving in a different direction to us,” said Professor Staveley-Smith.

Seen from Earth, but invisible to the human eye, the outflows stretch about two-thirds across the sky from horizon to horizon.

They match previously identified regions of gamma-ray emission detected with NASA’s Fermi Space Telescope (then-called “Fermi Bubbles”) and the “haze” of microwave emission spotted by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and Planck Space Telescope.

“Adding observations by the ground-based Parkes radio telescope to those made in the past by space telescopes finally allows us to understand how these enormous outflows are powered,” said Professor Staveley-Smith.

Previously it was unclear whether it was quasar-like activity of our Galaxy’s central super-massive black hole or star formation that kept injecting energy into the outflows.

The recent findings, reported in Nature today, show that the phenomenon is driven by many generations of stars forming and exploding in the Galactic Centre over the last hundred million years.

“We were able to analyse the magnetic energy content of the outflows and conclude that star formation must have happened in several bouts,” said CAASTRO Director Professor Bryan Gaensler.

Further analyses of the polarisation properties and magnetic fields of the outflows can also help us to answer one of astronomy’s big questions about our Galaxy.

“We found that the outflows’ radiation is not homogenous but that it actually reveals a high degree of structure – which we suspect is key to how the Galaxy’s overall magnetic field is generated and maintained,” said Professor Gaensler.

The research was led by Dr Ettore Carretti from the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation.

Further Information:

Professor Lister Staveley-Smith

Deputy Director

ICRAR The University of Western Australia, and CAASTRO

Mobile: +61 (0) 425 212 592

Email: lister.staveley-smith@uwa.edu.au

Kirsten Gottschalk

Media Contact, ICRAR

Mobile: +61 (0) 438 361 876

Email: kirsten.gottschalk@icrar.org

Dr Wiebke Ebeling

Media Contact, CAASTRO

Mobile: +61 (0) 423 933 444

Email: wiebke.ebeling@curtin.edu.au

Image:

The new-found outflows of particles (pale blue) from the Galactic Centre. The background image is the whole Milky Way at the same scale. The curvature of the outflows is real, not a distortion caused by the imaging process. Credit: Radio image – E. Carretti (CSIRO); Radio data – S-PASS team; Optical image – A. Mellinger (Central Michigan University); Image composition, E. Bressert (CSIRO).